How can one start with nothing, then end up with infinitely many things? Well, when one starts with a triangle whose slopes are not necessarily in geometric progression and then “enters inside” it; one obtains an assemblage of “smaller” triangles whose slopes are in geometric progression.

Desirable properties from sub-triangles

A sub-triangle is simply a (smaller) triangle contained in another triangle. It can share a side with the original triangle, its vertices can lie on the sides of the original triangle, or its vertices can lie completely inside the parent triangle.

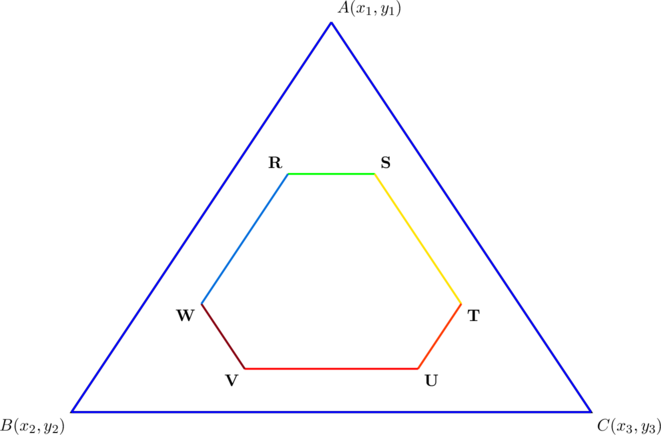

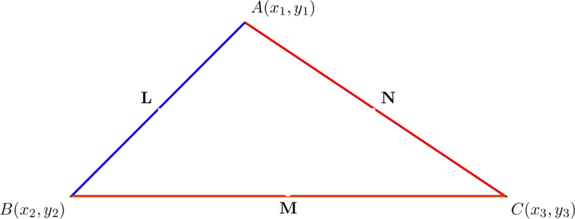

The medial triangle of any triangle is a good example of a sub-triangle in which its vertices lie on the midpoints of the sides of the original triangle (for instance, in the diagram below, ![]() is the medial triangle of

is the medial triangle of ![]() ).

).

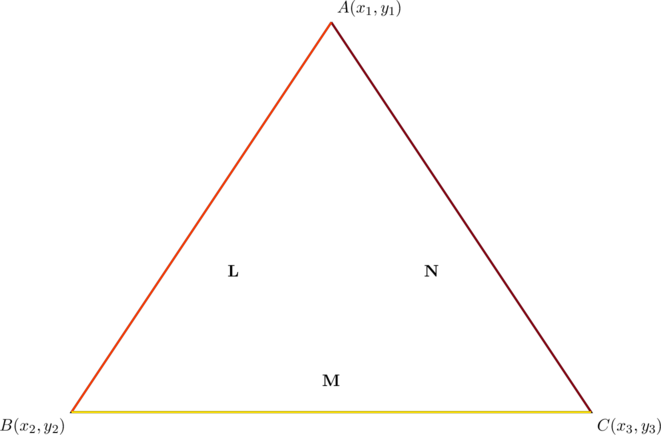

A sub-triangle can also lie completely inside the parent triangle, like below:

We show that any triangle with one side parallel to the ![]() -axis contains infinitely many sub-triangles with slopes in geometric progression; in particular, we obtain that “coveted” case in which the common ratio

-axis contains infinitely many sub-triangles with slopes in geometric progression; in particular, we obtain that “coveted” case in which the common ratio ![]() .

.

Example (THEOREM)

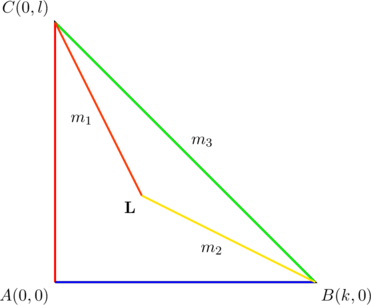

Let ![]() be a right triangle in which one leg is on the

be a right triangle in which one leg is on the ![]() -axis (or parallel to the

-axis (or parallel to the ![]() -axis). For any real number

-axis). For any real number ![]() ,

, ![]() , PROVE that there’s a sub-triangle of

, PROVE that there’s a sub-triangle of ![]() whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio

whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

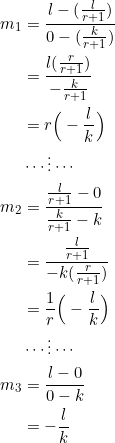

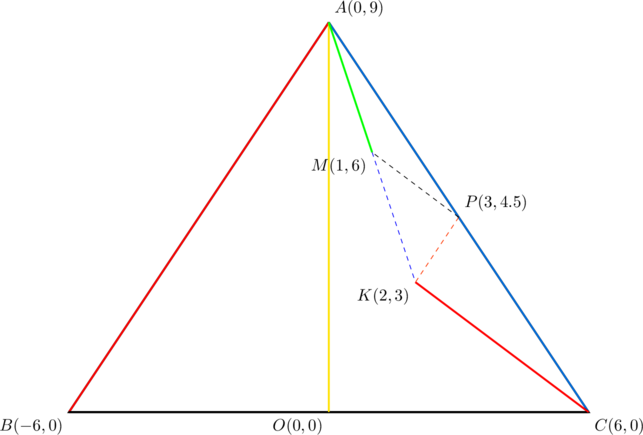

To make the proof simple, consider a right triangle ![]() with vertices at

with vertices at ![]() . Every other right triangle that fits the description in our “theorem” is a translation of the named

. Every other right triangle that fits the description in our “theorem” is a translation of the named ![]() , so no loss in generality.

, so no loss in generality.

![]() does the trick, if we define

does the trick, if we define ![]() . The essence of requiring a positive

. The essence of requiring a positive ![]() is to ensure that

is to ensure that ![]() lies inside the given triangle.

lies inside the given triangle.

Thus, the slope sequence ![]() is geometric, with common ratio

is geometric, with common ratio ![]() .

.

Considering how simple and basic the above proof is, does the result deserve the use of that reserved — and almost revered — word “theorem”? Or, should the “label” be reversed?

Example

PROVE that each of the sub-triangles constructed in Example 1 above contains an obtuse angle.

Recall the slopes: ![]() . Since the common ratio

. Since the common ratio ![]() is positive, it follows (depending on the sign of

is positive, it follows (depending on the sign of ![]() ) that the slopes of the sides are either all positive or all negative. Now, any triangle that contains all positive or all negative slopes must be obtuse-angled. (VERIFY this!)

) that the slopes of the sides are either all positive or all negative. Now, any triangle that contains all positive or all negative slopes must be obtuse-angled. (VERIFY this!)

Consequently, none of the sub-triangles constructed in Example 1 is equilateral or right-angled.

Example

For any right triangle with legs on the coordinate axes, PROVE that if the endpoints of the hypotenuse are joined to the centroid, then the slopes of the resulting sub-triangle form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

COOL!

Since the centroid has coordinates ![]() , this is the case of

, this is the case of ![]() in view of Example 1.

in view of Example 1.

Note that the same result holds when the legs are parallel to the coordinate axes.

Two times infinity

Not only do we get one sub-triangle for a given ![]() ; we actually get two — in fact, more!!!

; we actually get two — in fact, more!!!

Example

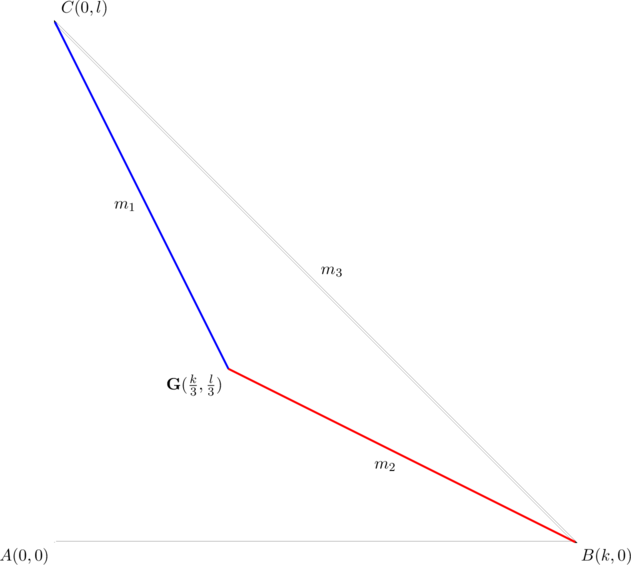

PROVE that every triangle with slopes ![]() contains a sub-triangle with slopes

contains a sub-triangle with slopes ![]()

We’ll apply the first proposition we established in our previous post; it states that the (non-zero) slopes of a triangle form a geometric progression if and only if there is a median whose slope is the negative of the slope of the side it meets.

Suppose that ![]() is such that sides

is such that sides ![]() have slopes

have slopes ![]() . Then the slope of the median from vertex

. Then the slope of the median from vertex ![]() is

is ![]() :

:

Let ![]() be the midpoint of

be the midpoint of ![]() and let

and let ![]() be the midpoint of

be the midpoint of ![]() . Join

. Join ![]() , the dashed red line segment shown above. Since

, the dashed red line segment shown above. Since ![]() connects the midpoints of two sides, it is parallel to the third side, namely

connects the midpoints of two sides, it is parallel to the third side, namely ![]() . So, the slope of

. So, the slope of ![]() is equal to the slope of

is equal to the slope of ![]() , which is

, which is ![]() . Furthermore, the slope of

. Furthermore, the slope of ![]() is

is ![]() , same as that of

, same as that of ![]() .

.

Thus, ![]() has slopes

has slopes ![]() for sides

for sides ![]() , respectively.

, respectively.

Note that there are actually two sub-triangles with slopes ![]() associated to a parent triangle with slopes

associated to a parent triangle with slopes ![]() .

.

Example (THEOREM)

Let ![]() be a non-right triangle in which one side is on the

be a non-right triangle in which one side is on the ![]() -axis (or parallel to the

-axis (or parallel to the ![]() -axis). For any real number

-axis). For any real number ![]() ,

, ![]() , PROVE that there’s a sub-triangle of

, PROVE that there’s a sub-triangle of ![]() whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio

whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

This follows from Example 1. Since one side is parallel to the ![]() -axis, draw an altitude from the opposite vertex. The two resulting right triangles both conform to the description in Example 1.

-axis, draw an altitude from the opposite vertex. The two resulting right triangles both conform to the description in Example 1.

Example (Main goal)

PROVE that every triangle with one side parallel to the ![]() -axis contains a sub-triangle in which one median is vertical and one median is horizontal.

-axis contains a sub-triangle in which one median is vertical and one median is horizontal.

The proof of Example 6 follows from Example 3 and Example 4.

EUREKA! Remember that “VHM” property? See here. Since the “VHM” property is extremely nice, we were curious as to whether it can be embedded into every triangle. Today’s post arose from that curiosity. We’ve now done it for triangles in which one side has zero slope; we’ll do something similar for general triangles.

Three times infinity

We improve on the number of sub-triangles we can have for any given ![]() .

.

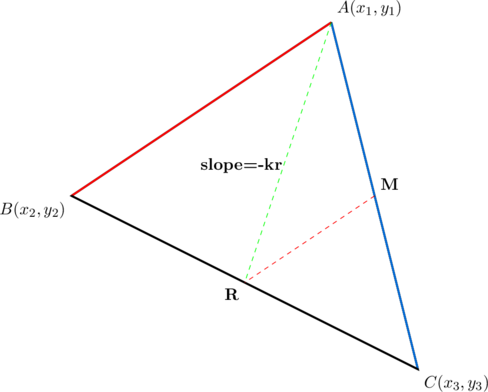

Example (Theorem)

PROVE that any right triangle with legs parallel to the coordinate axes contains three different sub-triangles whose slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() , where

, where ![]() .

.

We prove this for the right triangle ![]() with coordinates

with coordinates ![]() ; just a slight modification is needed for the general case when the legs are parallel to, but not on, the coordinate axes.

; just a slight modification is needed for the general case when the legs are parallel to, but not on, the coordinate axes.

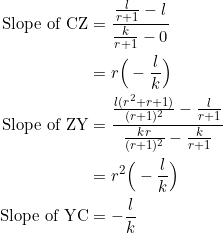

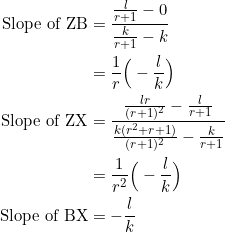

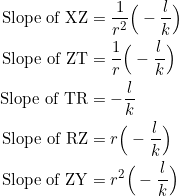

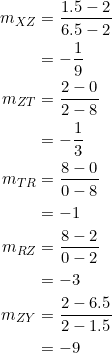

The desired sub-triangles, each with side slopes in geometric progression and common ratio ![]() , are:

, are: ![]() . Using the given coordinates, we can confirm this by calculating slopes:

. Using the given coordinates, we can confirm this by calculating slopes:

Thus, the slopes of the sides of ![]() differ by a constant multiple of

differ by a constant multiple of ![]() . Since we’ve already shown that the slopes of

. Since we’ve already shown that the slopes of ![]() differ by a constant multiple of

differ by a constant multiple of ![]() , it just remains to do the same for

, it just remains to do the same for ![]() .

.

Therefore, the slopes of the sides of ![]() form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

Observe that ![]() in the above diagram has side slopes also in geometric progression, but with common ratio

in the above diagram has side slopes also in geometric progression, but with common ratio ![]() .

.

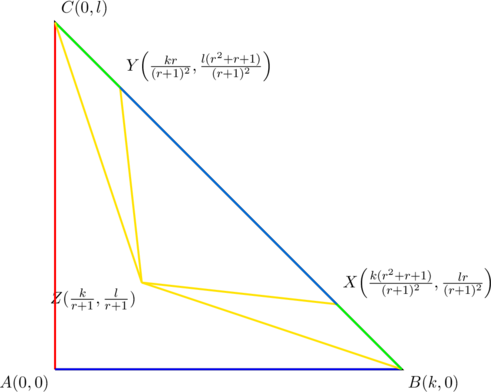

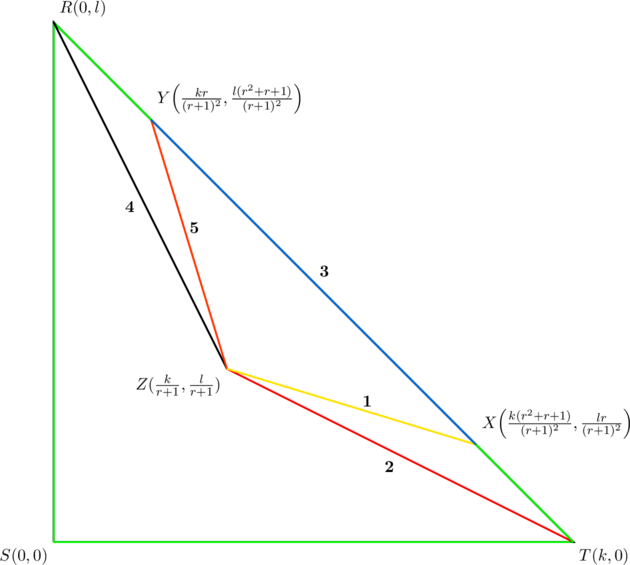

Example (zig-zag theorem)

For any right triangle ![]() with legs (

with legs (![]() ) on the coordinate axes, PROVE that there are points

) on the coordinate axes, PROVE that there are points ![]() and

and ![]() on the hypotenuse

on the hypotenuse ![]() and an interior point

and an interior point ![]() such that the slopes of

such that the slopes of ![]() form a five-term geometric progression.

form a five-term geometric progression.

Let the vertices of the right triangle ![]() be located at

be located at ![]() . For

. For ![]() , define

, define ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is an interior point of

is an interior point of ![]() ; further,

; further, ![]() and

and ![]() lie (internally) on the hypotenuse

lie (internally) on the hypotenuse ![]() . With the given coordinates, we have the following slopes:

. With the given coordinates, we have the following slopes:

These slopes differ by a constant multiple of ![]() . Notice how the line segments

. Notice how the line segments ![]() are traversed in a sort of “zig-zag” manner as shown below:

are traversed in a sort of “zig-zag” manner as shown below:

Numerical problems

Always a good idea to support theory with examples.

Example

Given ![]() with vertices at

with vertices at ![]() , find coordinates for its four sub-triangles that all satisfy the “VHM” property.

, find coordinates for its four sub-triangles that all satisfy the “VHM” property.

Note that the parent triangle doesn’t satisfy the “VHM” property; in particular, the ![]() -coordinates

-coordinates ![]() do not form an arithmetic progression, though the

do not form an arithmetic progression, though the ![]() -coordinates

-coordinates ![]() do.

do.

A sample sub-triangle is ![]() with vertices

with vertices ![]() shown above. Notice that its

shown above. Notice that its ![]() -coordinates

-coordinates ![]() form an arithmetic progression, as well as its

form an arithmetic progression, as well as its ![]() -coordinates

-coordinates ![]() .

.

How did we obtain ![]() ? Easy. We followed Example 3 and Example 4:

? Easy. We followed Example 3 and Example 4:

- divide the parent triangle into two right triangles (

and

and  )

) - find the centroids of each of the two resulting right triangles (for

it is

it is  )

) - connect the centroid to the endpoints of the hypotenuse (e.g., for

, join

, join  to

to  and

and  to

to  ; this way, the resulting triangle

; this way, the resulting triangle  has common ratio

has common ratio  )

) - connect the centroid to the midpoint of the hypotenuse (

in the diagram)

in the diagram) - join

to the midpoint of

to the midpoint of  (

( in the diagram). DONE.

in the diagram). DONE.

The centroid (![]() ), the midpoint of the hypotenuse (

), the midpoint of the hypotenuse (![]() ), and the midpoint of side

), and the midpoint of side ![]() (

(![]() ) are all we need. Repeating this process for the lower sub-triangle

) are all we need. Repeating this process for the lower sub-triangle ![]() as well as for the right triangle on the left, we obtain the following list of four sub-triangles satisfying that satisfying “VHM” property (you read that correctly):

as well as for the right triangle on the left, we obtain the following list of four sub-triangles satisfying that satisfying “VHM” property (you read that correctly):

;

; ;

; ;

; .

.

Of course, each is a peach.

Example

Given the right triangle ![]() with coordinates

with coordinates ![]() , find coordinates for two points

, find coordinates for two points ![]() and

and ![]() on

on ![]() and an interior point

and an interior point ![]() such that there is a five-term geometric progression for the slopes of

such that there is a five-term geometric progression for the slopes of ![]() .

.

Set ![]() . Then we have:

. Then we have:

Thus the slopes of the segments ![]() are

are ![]() , respectively. They form a five-term geometric progression with a common ratio of

, respectively. They form a five-term geometric progression with a common ratio of ![]() .

.

Having read through this page, it’s now too late to hate these greats — triangles with slopes in geometric progression.

Takeaway

Sometimes, you already have what you seek — if you look “within”. Does that seem to click?

As we’ve shown, a parent triangle may not have a desirable property on the surface, until its interior is examined. To look down on people — or things — solely on their outward look, is not cool.

Tasks

- (Embedded hexagon) For any triangle

, PROVE that it is possible to embed a hexagon whose vertices lie completely inside

, PROVE that it is possible to embed a hexagon whose vertices lie completely inside  , and such that three of its sides are

, and such that three of its sides are  the side lengths of

the side lengths of  and the remaining three are

and the remaining three are  the side lengths of

the side lengths of  .

.

(In the diagram above,

. Simply find the coordinates of

. Simply find the coordinates of  in terms of the coordinates of

in terms of the coordinates of  .)

.) - (Power two) Given

with vertices

with vertices  , the slopes of sides

, the slopes of sides  form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio  . Find coordinates for two points

. Find coordinates for two points  and

and  on

on  such that the slopes of the sides of

such that the slopes of the sides of  form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio  .

.

(Notice that . This is always possible for any triangle whose slopes form a geometric progression with a positive common ratio.)

. This is always possible for any triangle whose slopes form a geometric progression with a positive common ratio.) - (Power two) Given

with vertices

with vertices  , the slopes of sides

, the slopes of sides  form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio  . Find coordinates for two points

. Find coordinates for two points  and

and  on

on  such that the slopes of the sides of

such that the slopes of the sides of  form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio  .

.

(Notice that . This is always possible for any triangle whose slopes form a geometric progression with a positive common ratio.)

. This is always possible for any triangle whose slopes form a geometric progression with a positive common ratio.) - (Five terms) For any triangle

with slopes of sides

with slopes of sides  forming a geometric progression with positive common ratio, PROVE that there are points

forming a geometric progression with positive common ratio, PROVE that there are points  and

and  on

on  such that the slopes of the line segments

such that the slopes of the line segments  form a five-term geometric progression.

form a five-term geometric progression.

(This has very important implication and application. In particular, it helps us to associate every finite geometric sequence having a positive common ratio with a triangle.) - Given

with vertices

with vertices  , its slopes (

, its slopes ( ) are in geometric progression. PROVE that it contains a sub-triangle satisfying the following two properties:

) are in geometric progression. PROVE that it contains a sub-triangle satisfying the following two properties:

- its slopes are in arithmetic progression, namely

- the midpoint of one of its sides is the centroid of the original triangle.

(The above triangle has very nice properties; no wonder we’ve encountered it twice in these tasks.)

- its slopes are in arithmetic progression, namely

- (Two sequences) Let

be such that the slopes of sides

be such that the slopes of sides  form a geometric progression

form a geometric progression  with a positive common ratio

with a positive common ratio  . PROVE that there is a point

. PROVE that there is a point  on

on  , a point

, a point  on

on  , and a point

, and a point  on

on  such that the slopes of the sides of

such that the slopes of the sides of  form an arithmetic progression

form an arithmetic progression  .

. - Let

be such that the slopes of sides

be such that the slopes of sides  form a geometric progression, with a positive common ratio. PROVE that there are points

form a geometric progression, with a positive common ratio. PROVE that there are points  and

and  on

on  such that

such that  .

. - Let

be such that the slopes of sides

be such that the slopes of sides  form a geometric progression, with a negative common ratio. PROVE that there is a point

form a geometric progression, with a negative common ratio. PROVE that there is a point  on

on  and a point

and a point  on

on  such that

such that  .

.

(Apparently, negative common ratios change things slightly. Being biased, they are our favorite.) - (Internal division) Let

be a line segment, where

be a line segment, where  has coordinates

has coordinates  and

and  has coordinates

has coordinates  . For

. For  , PROVE that the point

, PROVE that the point  lies within

lies within  .

. - (Smaller lengths) PROVE that every triangle contains a sub-triangle whose lengths are

of the lengths of the original triangle, for any

of the lengths of the original triangle, for any  .

.