Two posts ago, we promised to discuss the general theory behind triangles whose sides have slopes of ![]() — and here we go!!! We also considered, in the previous post, triangles whose sides have slopes of the form

— and here we go!!! We also considered, in the previous post, triangles whose sides have slopes of the form ![]() . If you loved those two, and you read this one through, you’ll love this one too. Or even “befriend” it as we do.

. If you loved those two, and you read this one through, you’ll love this one too. Or even “befriend” it as we do.

That’s true.

Slopes in arithmetic progression

Example 1

Find coordinates for the vertices of a triangle whose sides have slopes of ![]() .

.

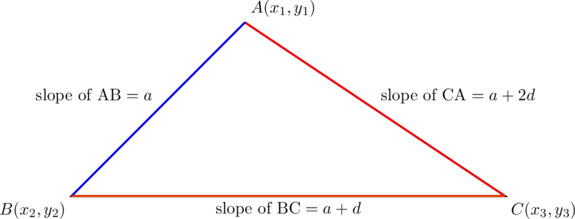

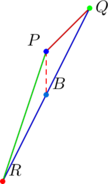

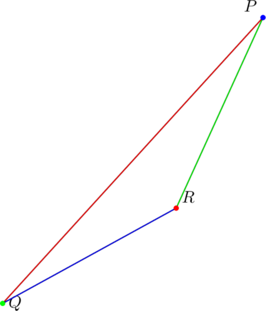

Let ![]() have vertices as shown below:

have vertices as shown below:

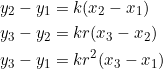

Since the slopes of sides ![]() are

are ![]() , respectively, we have the following linear equations:

, respectively, we have the following linear equations:

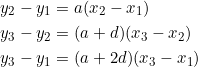

which we can recast into a “homogeneous” system:

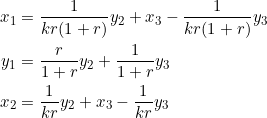

(1) ![]()

(2) ![]()

(3) ![]()

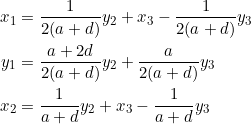

Notice that there are six unknowns in three equations, so the system is underdetermined. Being also homogeneous, it has an infinite number of solutions, as our friend from L.A. (a.k.a Linear Algebra, not Los Angeles), just informed us. By row reduction, our system is found to have a rank of ![]() as well as three degrees of freedom — the latter meaning that the solution can be expressed in terms of three parameters (or “free” variables). In fact, we have:

as well as three degrees of freedom — the latter meaning that the solution can be expressed in terms of three parameters (or “free” variables). In fact, we have:

where ![]() are our three “free” variables. Observe that the coefficients of these variables add up to one in the above equations, so in a sense they’re weighted.

are our three “free” variables. Observe that the coefficients of these variables add up to one in the above equations, so in a sense they’re weighted.

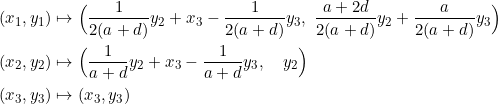

To sum up, the required coordinates are:

As you may have thought, the formula breaks down when ![]() , but this leads to an important special case that deserves a separate treatment.

, but this leads to an important special case that deserves a separate treatment.

Example 2

In the notation of our first diagram, PROVE that ![]() if, and only if,

if, and only if, ![]() .

.

This is immediate; just another way of saying that the slope of side ![]() is zero. However, if we want to be fancy, we can use equation (3). First assume that

is zero. However, if we want to be fancy, we can use equation (3). First assume that ![]() . Then (3) reduces to

. Then (3) reduces to ![]() . Conversely, if

. Conversely, if ![]() , then we’re left with

, then we’re left with

![]()

which in turn leaves us with two choices: ![]() or

or ![]() . However,

. However, ![]() is impossible because otherwise it would mean that

is impossible because otherwise it would mean that ![]() . Together with the fact that

. Together with the fact that ![]() (by the assumption in the converse), the points

(by the assumption in the converse), the points ![]() and

and ![]() will coincide, meaning that we don’t have a triangle. So we choose

will coincide, meaning that we don’t have a triangle. So we choose ![]() and this completes the proof.

and this completes the proof.

As a by-product, we also obtain that ![]() is equivalent to

is equivalent to ![]() . We’ll have more to say about this case later.

. We’ll have more to say about this case later.

Example 3

Find the ![]() -coordinate of the centroid of a triangle whose sides have slopes of

-coordinate of the centroid of a triangle whose sides have slopes of ![]() .

.

The ![]() -coordinate of the centroid is given by

-coordinate of the centroid is given by ![]() . Using the coordinates we found in Example 1, we have:

. Using the coordinates we found in Example 1, we have:

Example 4

PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle follow an arithmetic progression, then the triangle contains one vertical median.

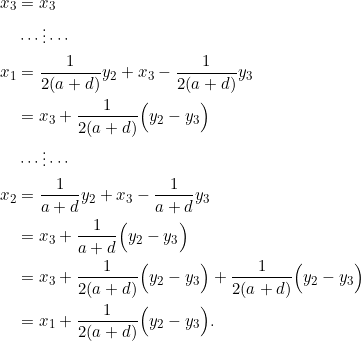

Let ![]() have vertices

have vertices ![]() and let sides

and let sides ![]() have slopes of

have slopes of ![]() , respectively. In Example 3, we saw that the

, respectively. In Example 3, we saw that the ![]() -coordinate of the centroid is precisely

-coordinate of the centroid is precisely ![]() . Since the centroid shares an

. Since the centroid shares an ![]() -coordinate with a triangle’s vertex (in this case

-coordinate with a triangle’s vertex (in this case ![]() ), we know — from our previous post — that the median through that vertex is vertical.

), we know — from our previous post — that the median through that vertex is vertical.

Example 5

PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle follow an arithmetic progression ![]() , then so do the x-coordinates.

, then so do the x-coordinates.

Note that the converse is not true.

To prove the above statement, we can use a result from our previous post, but let’s calculate it directly here. Enumerate the ![]() -coordinates as follows:

-coordinates as follows:

So the ![]() -coordinates differ consecutively by

-coordinates differ consecutively by ![]() .

.

The fact that the ![]() -coordinates follow an arithmetic progression whereas the

-coordinates follow an arithmetic progression whereas the ![]() -coordinates do not (necessarily) follow an arithmetic progression makes the resulting triangle diagram quite weird, which was what we called “ugly-looking” two posts ago.

-coordinates do not (necessarily) follow an arithmetic progression makes the resulting triangle diagram quite weird, which was what we called “ugly-looking” two posts ago.

Slopes in geometric progression

Example 6

Find coordinates for the vertices of a triangle whose sides have slopes of ![]() .

.

Of course, we want ![]() and

and ![]() . If there be any other restriction, it will become obvious when we’re done with the computations.

. If there be any other restriction, it will become obvious when we’re done with the computations.

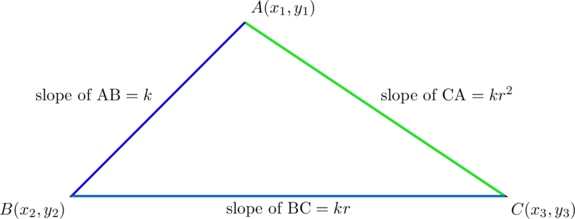

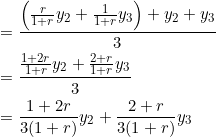

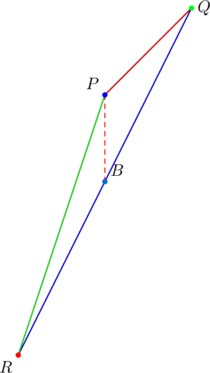

To find the coordinates, suppose we work with ![]() whose vertices are as shown below:

whose vertices are as shown below:

As before, it boils down to solving a linear system:

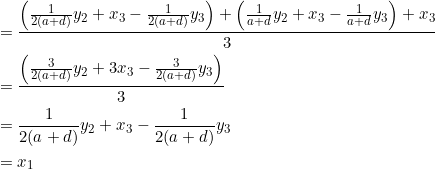

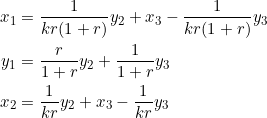

where, after row reduction and back-substitution, the solution is:

In each of the above expressions, the coefficients of the “free variables” ![]() add up to one, so in a sense they’re weighted.

add up to one, so in a sense they’re weighted.

Example 7

Find the centroid of the triangle with vertices given in Example 6 above.

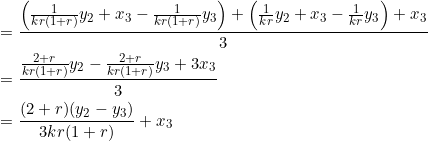

The ![]() -coordinate of the centroid is

-coordinate of the centroid is ![]() :

:

If ![]() , then the

, then the ![]() -coordinate coincides with

-coordinate coincides with ![]() . (Note that we can’t have

. (Note that we can’t have ![]() since otherwise one of the slopes will be zero, and we’re working with slopes in geometric progression.)

since otherwise one of the slopes will be zero, and we’re working with slopes in geometric progression.)

For the ![]() -coordinate of the centroid, we use

-coordinate of the centroid, we use ![]() :

:

If ![]() , the

, the ![]() -coordinate of the centroid coincides with

-coordinate of the centroid coincides with ![]() .

.

COOL.

Example 8

Let ![]() be such that sides

be such that sides ![]() have slopes

have slopes ![]() , respectively. PROVE that the slope of the median from vertex

, respectively. PROVE that the slope of the median from vertex ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

The fact that the slope of the median from vertex ![]() to side

to side ![]() and the slope of side

and the slope of side ![]() are negatives of each other has an important implication and application (see Example 9 below).

are negatives of each other has an important implication and application (see Example 9 below).

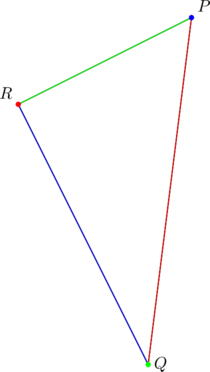

To prove the present statement, let’s refer to an earlier diagram:

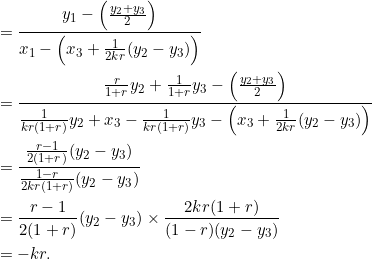

We found that

The midpoint of ![]() is

is ![]() and so the slope of the median from vertex

and so the slope of the median from vertex ![]() is:

is:

Example 9

Let ![]() be such that sides

be such that sides ![]() have slopes

have slopes ![]() , respectively. PROVE that

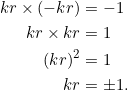

, respectively. PROVE that ![]() if, and only if,

if, and only if, ![]() .

.

Suppose that ![]() (a similar argument holds for

(a similar argument holds for ![]() ). By Example 8 above, the slope of the median from vertex

). By Example 8 above, the slope of the median from vertex ![]() is

is ![]() . But then this means that the median from vertex

. But then this means that the median from vertex ![]() is perpendicular to side

is perpendicular to side ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() and

and ![]() is isosceles.

is isosceles.

Conversely, suppose that ![]() . Then the median from vertex

. Then the median from vertex ![]() is perpendicular to side

is perpendicular to side ![]() , which in turn means that the product of their slopes is

, which in turn means that the product of their slopes is ![]() . Since their slopes are

. Since their slopes are ![]() and

and ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that

So we obtain a characterization of isosceles triangles, using slopes in geometric progression.

Example 10

Let ![]() be a right-triangle in which sides

be a right-triangle in which sides ![]() have slopes

have slopes ![]() , respectively. PROVE that

, respectively. PROVE that ![]() is necessarily negative, and that side

is necessarily negative, and that side ![]() cannot be the hypotenuse.

cannot be the hypotenuse.

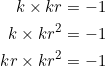

Since the location of the right-angle was not specified, we have to consider all possibilities. We use the fact that the product of the slopes of two perpendicular lines is ![]() , and take the product of two slopes at a time:

, and take the product of two slopes at a time:

From the first equation, ![]() , which is always negative because the denominator

, which is always negative because the denominator ![]() is always positive whatever (the real number)

is always positive whatever (the real number) ![]() is. From the third equation, we have

is. From the third equation, we have ![]() , and again

, and again ![]() is negative since it’s only the cube of a negative (real) number that can be negative.

is negative since it’s only the cube of a negative (real) number that can be negative.

Now from the second equation, we have ![]() . Since the left side of this equation is always positive whereas the right side is always negative, the equation doesn’t have real solution. In turn, this means that side

. Since the left side of this equation is always positive whereas the right side is always negative, the equation doesn’t have real solution. In turn, this means that side ![]() (with slope

(with slope ![]() ) and side

) and side ![]() (with slope

(with slope ![]() ) do not form a right-angle. Therefore, side

) do not form a right-angle. Therefore, side ![]() cannot be the hypotenuse.

cannot be the hypotenuse.

Numerical examples

We now move from the abstract angle to actual examples.

- Let

and

and  . Then the arithmetic sequence

. Then the arithmetic sequence  is

is  and the corresponding coordinates for the vertices of a triangle with slopes

and the corresponding coordinates for the vertices of a triangle with slopes  are:

are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[x_1=x_3+\frac{1}{4}(y_2-y_3),~y_1=\frac{3}{4}y_2+\frac{1}{4}y_3,~x_2=x_3+\frac{1}{2}(y_2-y_3).\]](//blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/plugins/a3-lazy-load/assets/images/lazy_placeholder.gif)

are “free” variables. We obtain an assemblage of triangles by specifying values for

are “free” variables. We obtain an assemblage of triangles by specifying values for  , so long as

, so long as  .

.- Put

and

and  . Then

. Then  . The resulting triangle has coordinates at

. The resulting triangle has coordinates at  :

:

Notice the presence of a vertical median

.

. - Put

and

and  . Then

. Then  . We obtain a triangle with coordinates at

. We obtain a triangle with coordinates at  :

:

Notice the presence of a vertical median

.

.

- Put

- Let

and

and  . Then the corresponding arithmetic sequence of slopes is

. Then the corresponding arithmetic sequence of slopes is  ; moreover:

; moreover:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[x_1=x_3-\frac{1}{2}(y_2-y_3),~y_1=\frac{3}{2}y_2-\frac{1}{2}y_3,~x_2=x_3-(y_2-y_3).\]](//blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/plugins/a3-lazy-load/assets/images/lazy_placeholder.gif)

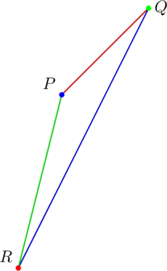

Depending on what we choose for the “free variables”, we obtain different sets of triangles. Let

. Then

. Then  . This results in a triangle with coordinates at

. This results in a triangle with coordinates at  :

:

Notice the presence of a vertical median

. Also this is a right triangle.

. Also this is a right triangle. - An example of a triangle with slopes in geometric progression. Let

and

and  ; the corresponding geometric sequence of slopes is

; the corresponding geometric sequence of slopes is  . If we put

. If we put  and

and  in our formula, we obtain

in our formula, we obtain

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[x_1=x_3+\frac{1}{6}(y_2-y_3),~y_1=\frac{4}{3}y_2-\frac{1}{3}y_3,~x_2=x_3-\frac{1}{2}(y_2-y_3).\]](//blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/plugins/a3-lazy-load/assets/images/lazy_placeholder.gif)

Next stop: choose values for the “free variables”

, bearing in mind that

, bearing in mind that  . Let

. Let  and

and  . We obtain

. We obtain  and the resulting triangle has vertices located at

and the resulting triangle has vertices located at  :

:

Notice that this is a right triangle.

- Let

and

and  ; we obtain the geometric sequence of slopes

; we obtain the geometric sequence of slopes  . In turn:

. In turn:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[x_1=x_3+\frac{1}{6}(y_2-y_3),~y_1=\frac{2}{3}y_2+\frac{1}{3}y_3,~x_2=x_3+\frac{1}{2}(y_2-y_3).\]](//blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/plugins/a3-lazy-load/assets/images/lazy_placeholder.gif)

For convenience, let’s choose our “free variables”

and

and  . We then obtain

. We then obtain  and a triangle with coordinates at

and a triangle with coordinates at  results:

results:

- Here’s an example in which some of the coordinates are irrational numbers. Let

and

and  . Let’s also choose our “free variables” right away:

. Let’s also choose our “free variables” right away:  and

and  . We obtain

. We obtain  and a triangle with coordinates at

and a triangle with coordinates at  results:

results:

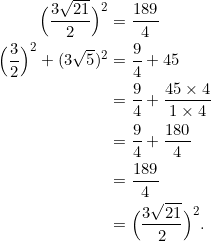

There’s something fascinating about this example that is worth mentioning. Observe that the given triangle doesn’t contain

. Now the midpoints of sides

. Now the midpoints of sides  are

are ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Big(3,\frac{3}{2}\sqrt{5}\Big),~\Big(2,\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\Big),~\Big(5,2\sqrt{5}\Big).\]](//blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/plugins/a3-lazy-load/assets/images/lazy_placeholder.gif)

Consequently, the lengths of the medians from

are

are  , respectively. How are these related?

, respectively. How are these related?

COOL.

Takeaway

If the slopes of the sides of a triangle are ![]() (a geometric progression), and the slopes of the sides of another triangle are

(a geometric progression), and the slopes of the sides of another triangle are ![]() (an arithmetic progression), then properties that correspond to

(an arithmetic progression), then properties that correspond to ![]() have analogues in

have analogues in ![]() . These properties are mainly lateral properties — isosceles or equilateral.

. These properties are mainly lateral properties — isosceles or equilateral.

We encourage you to investigate different cases of slopes in arithmetic progression and slopes in geometric progression. You’ll encounter exciting surprises.

Tasks

- PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle form a geometric progression

, then the slopes of its three medians also form a geometric progression (with a different common ratio), provided

, then the slopes of its three medians also form a geometric progression (with a different common ratio), provided  .

. - PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle form an arithmetic progression, then the slopes of its three medians do not form an arithmetic progression.

- Let

(

( ) be the slopes of the sides of a

) be the slopes of the sides of a  . PROVE that the product of the slopes of the three medians is

. PROVE that the product of the slopes of the three medians is  .

. - PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle are

, then the triangle can never be a right triangle.

, then the triangle can never be a right triangle.

Of course

Of course  .

.

- PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle are

, where

, where  and

and  are rational numbers, then the triangle can never be equilateral.

are rational numbers, then the triangle can never be equilateral.

Actually if either

Actually if either  or

or  is a rational number, same conclusion.

is a rational number, same conclusion.

- PROVE that if the slopes of the sides of a triangle are

, where

, where  and

and  are rational numbers, then the triangle can never be equilateral.

are rational numbers, then the triangle can never be equilateral.

It appears that equilateral triangles don’t like rational numbers?

It appears that equilateral triangles don’t like rational numbers?

- Let

be such that sides

be such that sides  have slopes

have slopes  , respectively. PROVE that the median from

, respectively. PROVE that the median from  and the median from

and the median from  can never intersect at

can never intersect at  , except when

, except when  .

.

Any triangle whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio

Any triangle whose side slopes form a geometric progression with common ratio  is a peach.

is a peach.

- PROVE that if the

-coordinates of the vertices of a triangle form an arithmetic progression, then the slopes of the sides do not necessarily form an arithmetic progression.

-coordinates of the vertices of a triangle form an arithmetic progression, then the slopes of the sides do not necessarily form an arithmetic progression.

A counter-example will do.

A counter-example will do.

- If the slopes of the sides of a triangle form a geometric sequence with a common ratio of

, PROVE that both the

, PROVE that both the  -coordinates and the

-coordinates and the  -coordinates form arithmetic progressions.

-coordinates form arithmetic progressions.

Cool.

Cool.

- Let

be such that sides

be such that sides  have slopes of

have slopes of  , respectively. PROVE that

, respectively. PROVE that  if, and only if

if, and only if  .

.

Pretend that you’re unaware of the Pythagorean theorem and perpendicular slopes. Solve the problem without recourse to these two.

Pretend that you’re unaware of the Pythagorean theorem and perpendicular slopes. Solve the problem without recourse to these two.

One thought on “Arithmetic and geometric slopes”

Comments are closed.