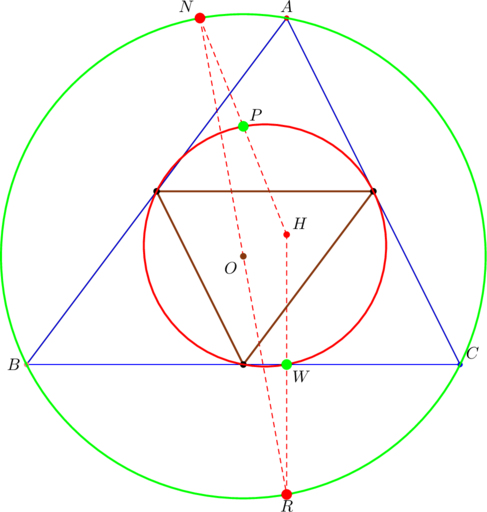

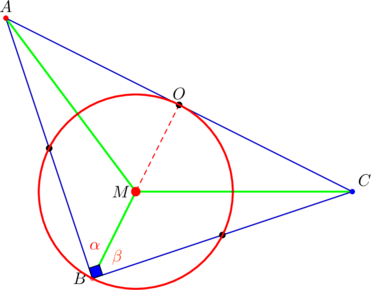

The picture which contains a mixture of the points we’ll constantly feature in most our posts this year is:

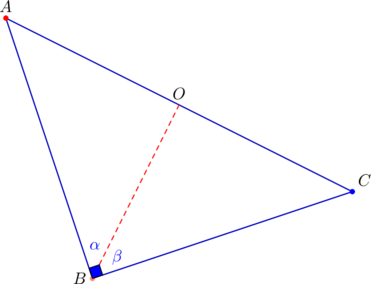

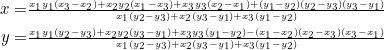

In furtherance of our previous post, we’re still discussing point ![]() , which one can easily pinpoint in the above picture. Its coordinates are given by

, which one can easily pinpoint in the above picture. Its coordinates are given by

(1)

relative to the vertices ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() of the parent triangle

of the parent triangle ![]() . It lies on the nine-point circle of

. It lies on the nine-point circle of ![]() , as we saw through numerous numerical examples previously (a proper proof will be provided later). In general,

, as we saw through numerous numerical examples previously (a proper proof will be provided later). In general, ![]() is distinct from the nine traditional points through which the nine-point circle passes (the mid-point of each side, the foot of each altitude, the midpoint of the line segment from the orthocenter to each vertex), and so we’ve chosen to call it “new”.

is distinct from the nine traditional points through which the nine-point circle passes (the mid-point of each side, the foot of each altitude, the midpoint of the line segment from the orthocenter to each vertex), and so we’ve chosen to call it “new”.

Today we focus on when our purportedly new point ![]() coincides with the nine traditional points through which the nine point circle passes. (For a clue as to what other new points are on the nine-point circle, see this article.)

coincides with the nine traditional points through which the nine point circle passes. (For a clue as to what other new points are on the nine-point circle, see this article.)

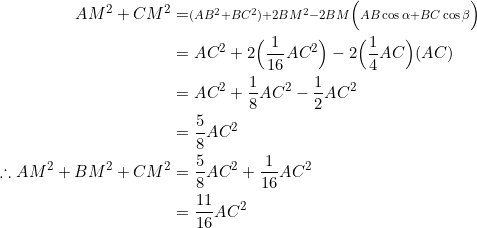

Eleven sixteenths

Remember the fraction: ![]() . And the caption.

. And the caption.

In example 2 below, we show that the sum of the squares of the distances from the center of the nine-point circle to the three vertices of a right triangle is always ![]() of the square of the hypotenuse. (Though not essential to today’s target, yet it’s what we won’t want you to forget.)

of the square of the hypotenuse. (Though not essential to today’s target, yet it’s what we won’t want you to forget.)

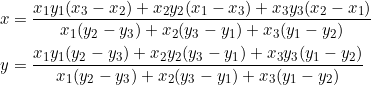

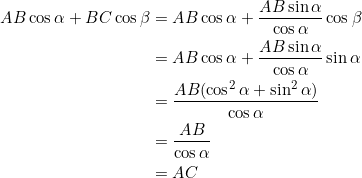

In the diagram below, PROVE that ![]() , given that

, given that ![]() is a median.

is a median.

Since ![]() is a median, the area of

is a median, the area of ![]() is equal to the area of

is equal to the area of ![]() :

:

![]()

Also, the sum of the areas of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() gives the area of the parent triangle

gives the area of the parent triangle ![]() :

:

We’ll now simplify ![]() using the fact that

using the fact that ![]() , obtained previously:

, obtained previously:

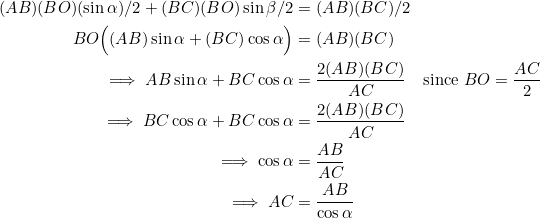

Let ![]() be the center of the nine-point circle of a right triangle

be the center of the nine-point circle of a right triangle ![]() , where

, where ![]() . PROVE that

. PROVE that ![]() .

.

Since the center ![]() of the nine-point circle is the midpoint of the orthocenter (

of the nine-point circle is the midpoint of the orthocenter (![]() ) and the circumcenter (

) and the circumcenter (![]() ) of

) of ![]() , we have that

, we have that

(2) ![]()

The cosine law, applied to ![]() and

and ![]() , gives:

, gives:

(3) ![]()

Add the two equations in (3) and use the fact that ![]() from example 1:

from example 1:

Elegant solution: CLICK to see

![]()

where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , as per usual notation. In the case of a right triangle with hypotenuse having length

, as per usual notation. In the case of a right triangle with hypotenuse having length ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() and then

and then ![]() . In turn:

. In turn:

![]()

Assuming one was not aware of the relation

![]()

there’s still another direct proof that’s simpler than the one we presented via examples 1 and 2 above. After solving a problem, always check for better solutions.

Please see exercise 3 for a non-right triangle where a modified version of the above result holds.

Equivalent statements

We now consider when the point ![]() with coordinates given in equation (1) coincides with the nine traditional points through which the nine-point circle passes. Our findings are easy to verify, so we skip the proofs.

with coordinates given in equation (1) coincides with the nine traditional points through which the nine-point circle passes. Our findings are easy to verify, so we skip the proofs.

coincides with the midpoint of

coincides with the midpoint of

- sides

and

and  have opposite slopes

have opposite slopes

In particular, for a right triangle, ![]() is precisely the circumcenter if and only if the legs have slopes

is precisely the circumcenter if and only if the legs have slopes ![]() .

.

Extraneous secret: CLICK to reveal

coincides with the foot of the altitude from vertex

coincides with the foot of the altitude from vertex

- side

is parallel to the

is parallel to the  -axis or parallel to the

-axis or parallel to the  -axis

-axis

Something extremely pleasant happens if we combine condition ![]() above with condition

above with condition ![]() below. See exercise 3 for the exquisite product.

below. See exercise 3 for the exquisite product.

coincides with the midpoint of the orthocenter and the foot of the altitude from vertex

coincides with the midpoint of the orthocenter and the foot of the altitude from vertex

- sides

and

and  have reciprocal slopes

have reciprocal slopes

Exclusive six

Our next set of equivalent statements ultimately pertain only to the right triangle — the right triangle with legs parallel to the coordinate axes.

, where

, where  is the orthocenter

is the orthocenter- two sides of the triangle are parallel to the coordinate axes

coincides with one of the triangle’s vertices

coincides with one of the triangle’s vertices- the slopes of the three medians form a geometric progression with common ratio

- the slopes of the three medians form an arithmetic progression with common difference equal to

times the first term (

times the first term ( )

) - one side of the triangle is parallel to the

-axis and another side and the median to it have opposite slopes.

-axis and another side and the median to it have opposite slopes.

A proper confluence of concepts right there. Among them all, the one that tickles our fancy the most is the fourth one, just because it has to do with that precious thing they call geometric progressions.

PROVE that if ![]() coincides with the orthocenter, then two sides of the triangle are parallel to the coordinate axes.

coincides with the orthocenter, then two sides of the triangle are parallel to the coordinate axes.

Despite the two different definitions of the line segments that yield them as points of concurrency, the orthocenter and our point ![]() have similar representations. For the orthocenter, the coordinates are:

have similar representations. For the orthocenter, the coordinates are:

(4)

and so if the two points coincide, then combining (1) and (4) gives

(5) ![]()

Only one factor from each equation can be zero. For example, let’s choose ![]() . Then in the second equation we can’t have

. Then in the second equation we can’t have ![]() . The choice is either

. The choice is either ![]() or

or ![]() . Whichever one is chosen, we’ll have one side parallel to the

. Whichever one is chosen, we’ll have one side parallel to the ![]() -axis (

-axis (![]() ) and another side parallel to the

) and another side parallel to the ![]() -axis (

-axis (![]() or

or ![]() ).

).

PROVE that if two sides of a triangle are parallel to the coordinate axes, then ![]() coincides with one of the triangle’s vertices.

coincides with one of the triangle’s vertices.

This is an application of example 4 above. Alternatively, suppose that ![]() and

and ![]() . Then, using equation (1) we have:

. Then, using equation (1) we have:

![]()

PROVE that if ![]() coincides with one of the vertices of a triangle, then the slopes of the three medians form a geometric progression with common ratio

coincides with one of the vertices of a triangle, then the slopes of the three medians form a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

(6) ![]()

We can’t have ![]() from the first equation. Otherwise, none of the factors in the second equation can be zero.

from the first equation. Otherwise, none of the factors in the second equation can be zero.

Let ![]() from the first equation. Then we can’t have

from the first equation. Then we can’t have ![]() in the second equation, and we can’t also have

in the second equation, and we can’t also have ![]() from the second equation. Only permissible option is

from the second equation. Only permissible option is ![]() . Thus, we have

. Thus, we have ![]() and

and ![]() , giving a triangle with two sides parallel to the coordinate axes.

, giving a triangle with two sides parallel to the coordinate axes.

Let ![]() from the first equation. Then, in the second equation, we can’t have

from the first equation. Then, in the second equation, we can’t have ![]() and we can’t have

and we can’t have ![]() . The only option remaining is

. The only option remaining is ![]() . Thus, we have

. Thus, we have ![]() and

and ![]() , again giving a triangle with two sides parallel to the coordinate axes.

, again giving a triangle with two sides parallel to the coordinate axes.

The rest of the proof now follows from example 9 here, or example 10 here.

PROVE that if a three-term geometric progression has common ratio ![]() , then it is an arithmetic progression when re-arranged.

, then it is an arithmetic progression when re-arranged.

We’re doing the easy proofs. Let the first term of the progression be ![]() . Since the common ratio

. Since the common ratio ![]() is

is ![]() , enumerate the geometric progression as

, enumerate the geometric progression as

![]()

and then interchange the first and second terms

![]()

to obtain an arithmetic progression in which the common difference is ![]() .

.

PROVE that if a three-term arithmetic progression has a common difference ![]() (

(![]() being the first term), then it is a geometric progression with common ratio

being the first term), then it is a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() when re-arranged.

when re-arranged.

Let the first term of the arithmetic progression be ![]() . Since the common difference is

. Since the common difference is ![]() , enumerate the terms as

, enumerate the terms as

![]()

and then re-arrange them as

![]()

The latter is a geometric progression with common ratio ![]() .

.

It remains to show that ![]() to complete the equivalence. Quite Easily Done.

to complete the equivalence. Quite Easily Done.

Takeaway

For ![]() with vertices

with vertices ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , the following statements are equivalent:

, the following statements are equivalent:

coincides with the foot of the altitude from vertex

coincides with the foot of the altitude from vertex

- side

is parallel to the

is parallel to the  -axis or is parallel to the

-axis or is parallel to the  -axis

-axis - the slopes of the three medians form an arithmetic progression with common difference

, or the reciprocals of the slopes of the three medians form an arithmetic progression with common difference

, or the reciprocals of the slopes of the three medians form an arithmetic progression with common difference  .

.

![]() o

o![]() .

.

Tasks

- In a right triangle, PROVE that

coincides with the circumcenter if and only if the slopes of the legs are

coincides with the circumcenter if and only if the slopes of the legs are  .

. - (Likely converse) In

, let

, let  . If a point

. If a point  is such that

is such that  , is

, is  the nine-point center of

the nine-point center of  ?

? - (Losing count) This exercise relates to a special triangle, representative of all triangles with one side parallel to the

-axis and the two other sides having reciprocal slopes. Let

-axis and the two other sides having reciprocal slopes. Let  ,

,  ,

,  be the coordinates of the vertices of

be the coordinates of the vertices of  . Assuming

. Assuming  , PROVE that:

, PROVE that:

- the slopes of sides

and

and  are reciprocals of each other

are reciprocals of each other - the nine-point center of

lies on side

lies on side

- the circumcenter of

lies on a line through vertex

lies on a line through vertex  and parallel to side

and parallel to side

- the foot of the altitude from vertex

is precisely the midpoint of the line segment joining

is precisely the midpoint of the line segment joining  to the orthocenter

to the orthocenter

- the foot of the altitude from vertex

is precisely the point

is precisely the point

- the circum-radius

satisfies

satisfies

- the slope of the Euler line cannot be

, where

, where  is the nine-point center (compare with example 2)

is the nine-point center (compare with example 2)

- the point

lies on the circumcircle of

lies on the circumcircle of

, where

, where  is the point given above

is the point given above , so

, so  is a diameter of the circumcircle of

is a diameter of the circumcircle of

, where

, where  is the orthocenter of

is the orthocenter of

- the orthic triangle is always isosceles

- the orthic triangle is equilateral, if

- the parent

is isosceles when

is isosceles when

- the circum-radius equals one of the side-lengths when

.

.

- the slopes of sides

- PROVE that the following statements are equivalent:

coincides with the midpoint of

coincides with the midpoint of

- sides

and

and  have opposite slopes

have opposite slopes - the area of

is

is  or

or

- Consider

in which

in which  ,

,  , and

, and  . If vertex

. If vertex  is extended to point

is extended to point  on the circumcircle in such a way that

on the circumcircle in such a way that  is parallel to

is parallel to  , PROVE that:

, PROVE that:

is a diameter of the circumcircle

is a diameter of the circumcircle

(so we also have

(so we also have  ).

).