In the case of ![]() with side-slopes

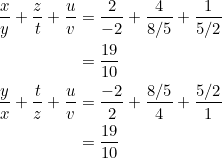

with side-slopes ![]() , the sum we formed in our last post becomes:

, the sum we formed in our last post becomes:

(1) ![]()

For certain, things always turn out interesting in the setting of geometric progressions. As ascertained in example 3 for instance, the order of each quotient in each summand can be reversed, while the final sum remains preserved:

(2) ![]()

Another interes-thing that pertains to this familiar terrain is how we obtain specific values when we restrict to equilateral and right isosceles triangles (spoiler alert: ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

How come???

In ![]() , let sides

, let sides ![]() have slopes

have slopes ![]() . PROVE that the slopes of the medians from each vertex are:

. PROVE that the slopes of the medians from each vertex are: ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Observe that the median slopes ![]() form a geometric progression. Except for the special case

form a geometric progression. Except for the special case ![]() , the slopes of the sides of a triangle form a geometric progression if and only if the slopes of the medians form another geometric progression, and their common ratios are related.

, the slopes of the sides of a triangle form a geometric progression if and only if the slopes of the medians form another geometric progression, and their common ratios are related.

Why does the case ![]() fail the equivalence? First, it is the required restriction in the median slopes stated above. Another reason is that any three-term geometric progression with common ratio

fail the equivalence? First, it is the required restriction in the median slopes stated above. Another reason is that any three-term geometric progression with common ratio ![]() is, upon re-arrangement, an arithmetic progression (for example,

is, upon re-arrangement, an arithmetic progression (for example, ![]() is geometric while

is geometric while ![]() is arithmetic). And if the side-slopes of a triangle form an arithmetic sequence, then the triangle necessarily contains a vertical median.

is arithmetic). And if the side-slopes of a triangle form an arithmetic sequence, then the triangle necessarily contains a vertical median.

In other to obtain ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , we’ll place the vertices of

, we’ll place the vertices of ![]() at the points

at the points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Since the slopes of sides

. Since the slopes of sides ![]() are

are ![]() respectively, the coordinates of the vertices are related according to:

respectively, the coordinates of the vertices are related according to:

(3) ![]()

Thus, the midpoint of ![]() is

is ![]() . In view of the above relations, we get

. In view of the above relations, we get ![]() . The slope of the median from vertex

. The slope of the median from vertex ![]() can then be obtained:

can then be obtained:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \begin{split} m_A&=\left[\left(\frac{y_2+y_3}{2}\right)-\left(\frac{ry_2+y_3}{r+1}\right)\right]\div\left[\left(x_3+\frac{y_2-y_3}{2ar}\right)-\left(x_3+\frac{y_2-y_3}{ar(r+1)}\right)\right]\\ &=\frac{(1-r)(y_2-y_3)}{2(r+1)}\div \frac{(r-1)(y_2-y_3)}{2ar(r+1)}\\ &=-ar. \end{split} \end{equation*}](https://blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-87a2c29439c994a8d3d7e2afb82ca3bb_l3.png)

The midpoint of ![]() is

is ![]() , as per (3). The slope of the median from vertex

, as per (3). The slope of the median from vertex ![]() is:

is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \begin{split} m_B&=\left[\frac{ry_2+(r+2)y_3-2(r+1)y_2}{2(r+1)}\right]\div\left[\frac{(y_2-y_3)-(2r+2)(y_2-y_3)}{2ar(r+1)}\right]\\ &=\frac{-(r+2)(y_2-y_3)}{2(r+1)}\div\frac{-(2r+1)(y_2-y_3)}{2ar(r+1)}\\ &=\left(\frac{r+2}{2r+1}\right)ar. \end{split} \end{equation*}](https://blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-771562e28aaa96664e876838fc04ec80_l3.png)

Similar calculation gives ![]() . Easy stuff.

. Easy stuff.

Derivations

Derive equation (1): ![]() for triangle

for triangle ![]() with sides

with sides ![]() having slopes

having slopes ![]() .

.

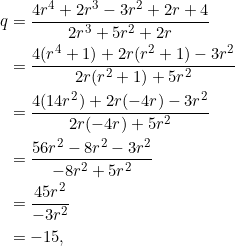

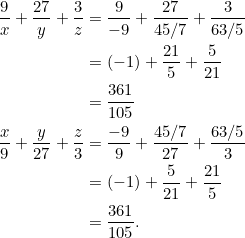

Using our definition of ![]() and the preceding example:

and the preceding example:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \begin{split} q&=\frac{m_{BC}}{m_A}+\frac{m_{CA}}{m_B}+\frac{m_{AB}}{m_C}\\ &=\frac{ar}{-ar}+\left[ar^2\div\left(\frac{r+2}{2r+1}\right)ar\right]+\left[a\div\left(\frac{2r+1}{r+2}\right)ar\right]\\ &=(-1)+\left(\frac{r(2r+1)}{r+2}\right)+\left(\frac{r+2}{r(2r+1)}\right)\\ &=\frac{-r(r+2)(2r+1)+r^2(2r+1)^2+(r+2)^2}{r(r+2)(2r+1)}\\ &=\frac{4r^4+2r^3-3r^2+2r+4}{2r^3+5r^2+2r}. \end{split} \end{equation*}](https://blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-2025325ad8cb52ef4d310596765bbfcb_l3.png)

Consequently, triangles having slopes in geometric progressions with the same common ratios have the same ![]() -values. And it is even possible to have different common ratios yielding the same

-values. And it is even possible to have different common ratios yielding the same ![]() -values.

-values.

PROVE that ![]() for

for ![]() with sides

with sides ![]() having slopes

having slopes ![]() respectively.

respectively.

Thus, we can use either equation (1) or equation (2) to compute ![]() in the case of geometric progressions. Using example 1 again:

in the case of geometric progressions. Using example 1 again:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{equation*} \begin{split} \frac{m_{A}}{m_{BC}}+\frac{m_{B}}{m_{CA}}+\frac{m_{C}}{m_{AB}}&=\frac{-ar}{ar}+\left[\left(\frac{r+2}{2r+1}\right)ar\div ar^2\right]+\left[\left(\frac{2r+1}{r+2}\right)ar\div a\right]\\ &=(-1)+\frac{r+2}{r(2r+1)}+\frac{r(2r+1)}{r+2}\\ &=\frac{-r(r+2)(2r+1)+(r+2)^2+r^2(2r+1)^2}{r(r+2)(2r+1)}\\ &=\frac{4r^4+2r^3-3r^2+2r+4}{2r^3+5r^2+2r}\\ &=\frac{m_{BC}}{m_A}+\frac{m_{CA}}{m_B}+\frac{m_{AB}}{m_C}. \end{split} \end{equation*}](https://blog.fridaymath.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f34afa06282754e8c81237b0a9e7c397_l3.png)

Notice that the coefficients in the numerator and denominator both add up to ![]() . Furthermore, the “symmetric” nature of these coefficients allows for easy calculations in some situations.

. Furthermore, the “symmetric” nature of these coefficients allows for easy calculations in some situations.

Demonstrations

Let ![]() be equilateral with side-slopes

be equilateral with side-slopes ![]() . PROVE that

. PROVE that ![]() .

.

There’s an important quadratic equation satisfied by the common ratio of the geometric progression formed by the slopes of an equilateral triangle:

![]()

It’s the key to obtaining ![]() , together with equation (1) and simple algebraic manipulations.

, together with equation (1) and simple algebraic manipulations.

where we’ve used the implications

![]()

Let ![]() be right isosceles with side-slopes

be right isosceles with side-slopes ![]() . PROVE that

. PROVE that ![]() .

.

Similar to the above, in a right isosceles triangle with side-slopes ![]() , the common ratio

, the common ratio ![]() satisfies the quadratic equation

satisfies the quadratic equation

![]()

Using equation (1) and a couple of simplifications, we find:

where the implications

![]()

were used in the simplifications.

Deductions

Suppose that a triangle with side-slopes ![]() satisfies

satisfies ![]() . Deduce that

. Deduce that ![]() .

.

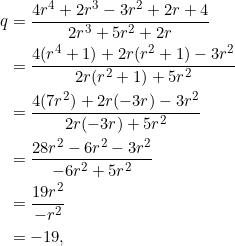

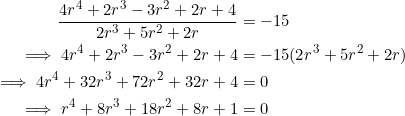

Quite interesting. Set ![]() in equation (1):

in equation (1):

Let’s show a few steps leading to the factorization of the quartic ![]() . If we apply the rational root theorem, the only values of

. If we apply the rational root theorem, the only values of ![]() worth testing are

worth testing are ![]() , none of which are roots of the quartic. However, the nature of the coefficients means that if two (quadratic) factors exist, they must both be monic and also have

, none of which are roots of the quartic. However, the nature of the coefficients means that if two (quadratic) factors exist, they must both be monic and also have ![]() as the constant terms. Put

as the constant terms. Put

![]()

and expand the right side:

![]()

Compare coefficients of like terms:

![]()

The above linear-quadratic system is satisfied only by ![]() . So we have the factorization

. So we have the factorization

![]()

In turn, ![]() , as desired.

, as desired.

Suppose that a triangle with side-slopes ![]() satisfies

satisfies ![]() . Deduce that

. Deduce that ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

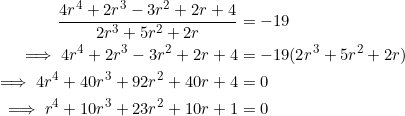

Put ![]() in equation (1):

in equation (1):

Set

![]()

and expand the right side:

![]()

Compare coefficients of like terms:

![]()

The above linear-quadratic system is satisfied only by ![]() (or

(or ![]() ,

, ![]() ). So we have the factorization

). So we have the factorization

![]()

In turn, ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

Digression

A simple connection between the preceding discussion and something else.

Find six distinct non-zero rational numbers ![]() which satisfy the relation

which satisfy the relation ![]() .

.

The non-zero requirement is somewhat redundant, being already forced by the fact that all six numbers appear in the denominators.

One way of solving this problem is to turn to slopes. In equations (1) and (2) we had

![]()

and so we can set

![]()

where ![]() are the slopes of the sides of a triangle which form a geometric progression, and

are the slopes of the sides of a triangle which form a geometric progression, and ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are the corresponding median slopes. We can find these slopes without specifying coordinates!

are the corresponding median slopes. We can find these slopes without specifying coordinates!

Any geometric progression (except the one with ![]() ) will do. Choose

) will do. Choose

![]()

Then ![]() can be obtained (in view of example 1) as

can be obtained (in view of example 1) as

![]()

Thus

![]()

The fractions now become

Equal.

Find three rational numbers ![]() , not all integers, which satisfy

, not all integers, which satisfy ![]() .

.

Were it not for the not all integers requirement, we could easily have chosen ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Instead, we turn to slopes again.

. Instead, we turn to slopes again.

Since the numbers ![]() form a geometric progression, we can associate them with the slopes of the sides of a triangle. Like so:

form a geometric progression, we can associate them with the slopes of the sides of a triangle. Like so:

![]()

Then the slopes of the medians would be:

![]()

The fractions become

Is the triple ![]() the only not all integers solution?

the only not all integers solution?

Find the slopes of the sides of a triangle if the median slopes are ![]() .

.

Since the median slopes form a geometric progression (with common ratio ![]() ), so must the side-slopes.

), so must the side-slopes.

From example 1, if the side slopes are ![]() , then the geometric mean of the median slopes is

, then the geometric mean of the median slopes is ![]() ; that is,

; that is,

![]()

Also, the common ratio ![]() of the median slopes is related to the common ratio

of the median slopes is related to the common ratio ![]() of the side-slopes via

of the side-slopes via

![]()

The side-slopes are then:

![]()

Takeaway

The following statements are equivalent for a triangle with slopes in geometric progression:

-

;

; - the common ratio

satisfies

satisfies  ;

; - the common ratio is that of an equilateral triangle.

Similarly, the following statements are equivalent for a triangle with slopes in geometric progression:

-

;

; - the common ratio

satisfies

satisfies  or

or  .

.

Finally:

![]()

Remember the name: exquisite equation.

Tasks

- Solve the rational equation

.

. - (Golden quartic) Let

be the golden ratio. PROVE that

be the golden ratio. PROVE that  .

. - (Related ratios) Suppose that the slopes of the sides of

form a geometric progression with common ratio

form a geometric progression with common ratio  . PROVE that the slopes of the medians form another geometric progression with common ratio

. PROVE that the slopes of the medians form another geometric progression with common ratio  , where

, where  .

. - Let

be an integer. PROVE that

be an integer. PROVE that  is also an integer if, and only if,

is also an integer if, and only if,  .

.

(If is not an integer,

is not an integer,  can still be an integer, as in the next exercise.)

can still be an integer, as in the next exercise.) - If

, PROVE that

, PROVE that  .

. - Let

be the slopes of sides

be the slopes of sides  in

in  . PROVE that

. PROVE that  .

. - Let

be the slopes of sides

be the slopes of sides  in

in  . PROVE that:

. PROVE that:

is a ratio of perfect squares if

is a ratio of perfect squares if  is a rational number.

is a rational number.

- Consider

with vertices at

with vertices at  ,

,  ,

,  . Verify that:

. Verify that:

- the side-slopes do not form a geometric progression

.

.

- Find the slopes of the sides of a triangle, if:

- the slopes of the medians are

;

; - the slopes of the medians are

;

; - the slopes of the medians are

.

.

- the slopes of the medians are

- Find distinct rational numbers

which satisfy the relation

which satisfy the relation